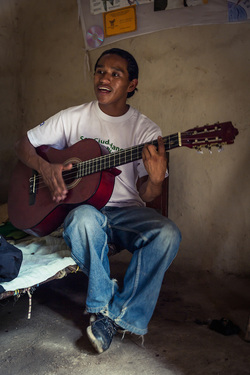

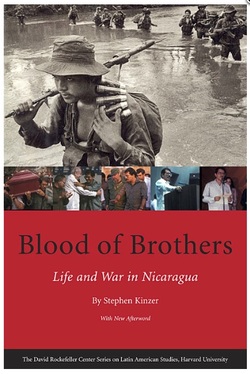

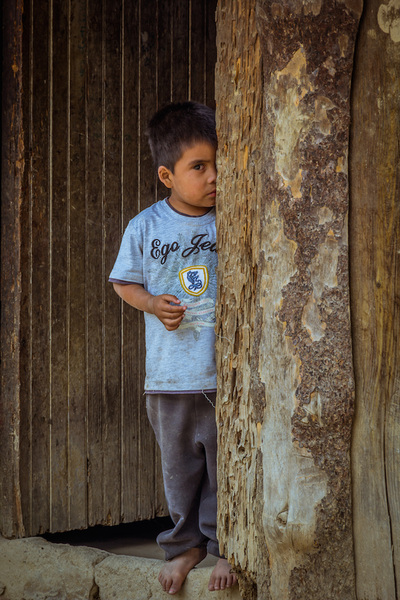

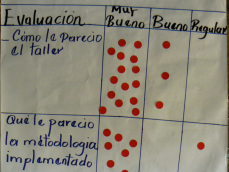

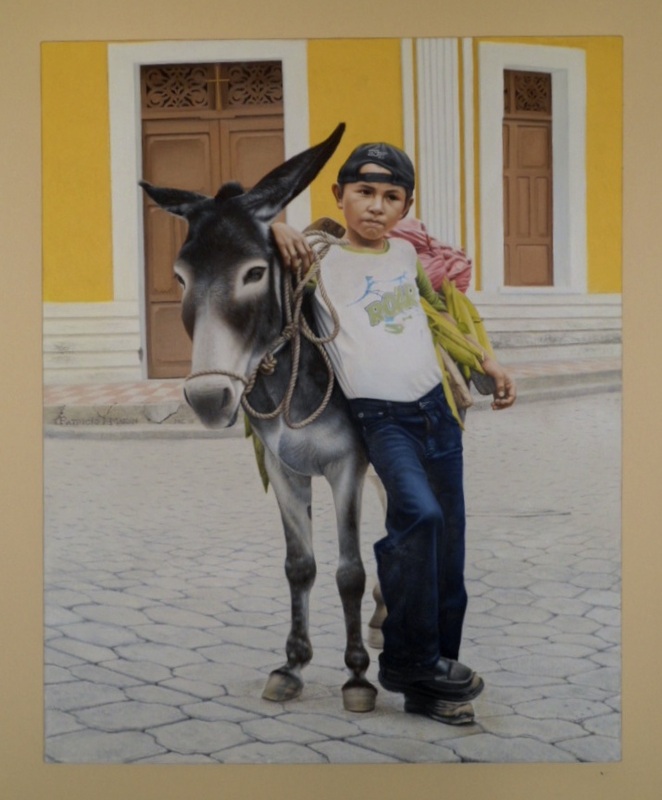

Cusmapa, Nueva Segovia, Nicaragua Lennin (photo by Osman Rivas) Lennin (photo by Osman Rivas) This is about a friendship I am grateful to have made... Lennin is from San José de Cusmapa, a town of about 7,000 people, close to the Honduran border and within sight of El Savador. It´s´a poor, rural community which is dry and short of water and work. The primary cash crop is coffee, which has all but been destroyed by disease. The remaining agriculture is subsistence. It is a town largely populated by indigenous people...people such as Lennin. I first met Lennin at a workshop in the institute where I volunteer. I was attracted to him more than others because he sings, simply and hauntingly, songs that are politically and/or socially motivated. He is passionate about the rights of indigenous people. He has no job (he works day jobs when he can get them), has very little money, and volunteers for the organization that represents indigenous people in Cusmapa...passionately. You can get a sense for his town by watching the short video at this link. I got to know Lennin's history when he took the 3-hour journey from his town to Ocotoal, a tedious journey along largely unpaved roads, that are only now in the beginning stages of being paved. I worked with him to create a website for the indigenous community of Cusmapa, something that felt like putting a contemporary "stake in the ground", although of little practical use in Nicaragua, where internet access outside the cities is limited and expensive for local people to buy, even if only by the hour.  The struggle of indigenous people in Nicaragua is probably not unlike many other countries, although the laws themselves seem pretty comprehensive here. However, I sense the application of the law may not always be so consistent. Lennin plays an active and passionate role in fighting for the rights of his people...especially through his music. So we also created a simple website for his music. You can sample his music (sung in Spanish), cheaply recorded on my Zoom H4 in a home-made recording studio in the flat I rent in Ocotal. Click here to hear his songs. Given the right equipment and someone who knows what he or she is doing, and it would sound a whole lot better.  Tona, Lennin's Mum (photo by Osman Rivas) Tona, Lennin's Mum (photo by Osman Rivas) It never ceases to amaze me that the when poor people are generous, their contribution seems so much greater than when rich people are generous. Which may not be fair, but proportionally, their contribution is much larger. Tona, Lennins's Mum, with little enough money to feed the family she had, adopted a young, under-nourished boy into the family and lavished him with love and a home. Working with the Fabretto organization, you can see a short video of the boy, Gabriel, and Tona at this link. The video provides a sense of the humble and happy home Gabriel has joined. A few years later, this video was made by the Fabetto organization, to show Gabriel's progress. It is a touching video and beautifully produced. Sadly it is not sub-titled, but if you understand Spanish, expect to shed a tear or two. The video is mixture of sadness, joy and unconditional love. The cynic in me could poo-poo the video as a manipulative promotional piece by a big NGO. But having visited the town, met and spent time with the family, and having eaten with Gabriel and Tona (beans, cheese and home-made corn tortillas, hot off the wood-burning stove), nothing bout the video is inauthentic. More to the point, Tona's every bit as beautiful as she is in the video. I am grateful for the rich opportunity to know Lennin because I am beginning (and I mean "beginning") to understand the roots of his plight and the plight of poor rural and indigenous people in Nicaragua.  The author, Kinzer, describes how Cesar Sandino's 1927-33 anti-U.S. campaign shaped the country's political development and inspired the overthrow of the Somoza regime in 1979. He analyzes the Reagan administration's "secret war" against the Sandinistas, and the deception that the contras existed only to interdict arms shipments to El Salvador. He paints a devastatingly sad and depressing picture of corruption, ineptitude and power-struggles. Reading the book, it would have been easy to sink into despair, had it not been for the resilience of Nicaragua's people. And a sense of compassion for the situation in contemporary Nicaragua. I am not a patient man In fact ,in an evaluation of my work here in the institute over the last two years (a team-wide, 360, in person evaluation - something you could never pull off in most corporate environments), my lack of patience and my lack of appreciation of Nicaraguan history and culture were my most significant learning edges. And I thought, wrongly as it seems, that this would be a strength after living overseas for 38 years! I could defend my intention (which clearly wasn't the "impact") as high expectations for what I thought was possible. However, reading this book just as I am about to leave, it is really helping me to reframe my disappointment as I begin to understand the history of this country. So I am grateful for the opportunity to know Lennin, his family - their daily joys and their daily struggles. What I experience through them in real life brings more of the words of the Kinzer's pages to life.

2 Comments

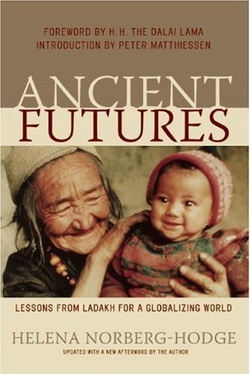

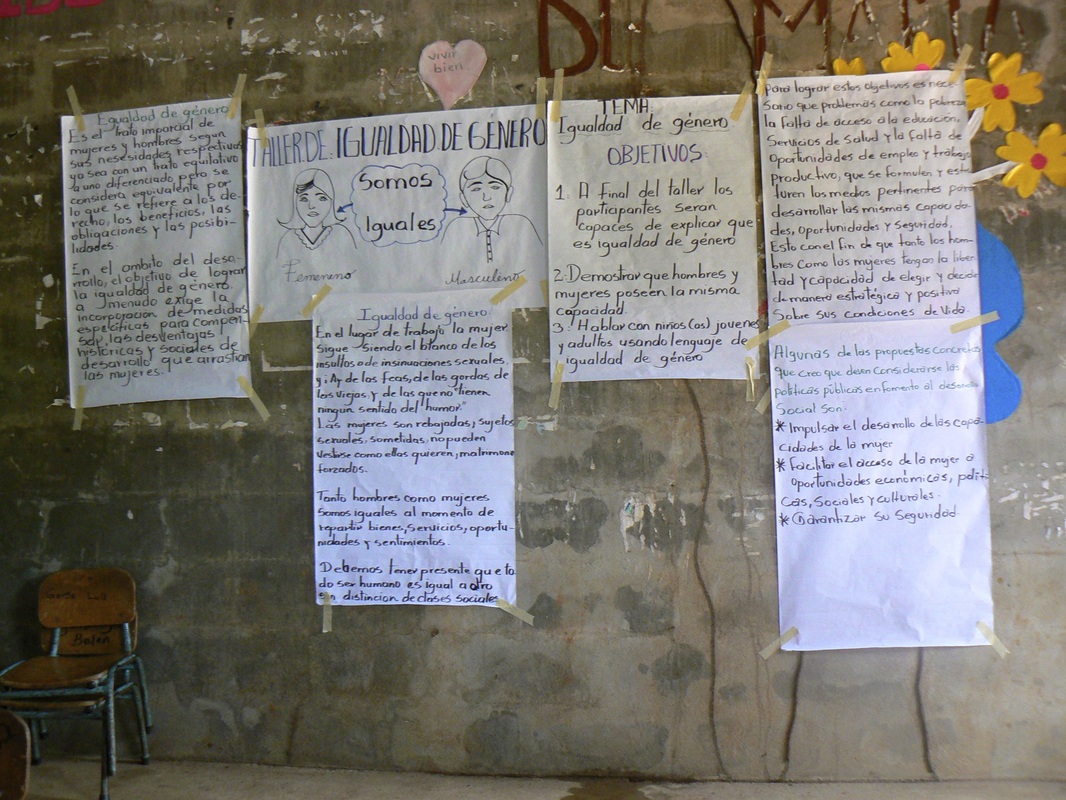

I am about 3 weeks away from leaving Nicaragua. When I leave, I will have been here for just under two years... I sold house, car and most of my furniture to relocate to one of the poorest regions of the country to build out my resume with experience working at the bottom of the pyramid, while contributing in some small way to an institute that seemed a perfect match to my previous experience, which was working at the top of the pyramid, and my future thinking, to work in some small way to close tha gap between the top and the bottom. I will leave feeling disappointed, defeated and just a little lost. The fault is not the institute where I have worked, but the bigger development system and political environment within which they so diligently work. Since I view the bigger system completely broken, I therefore see myself in any role within the system as aiding and abetting the problem. I´m not sure how to change it. On a recent trip to Quilali - a remote rural town about 2.5 hours away by truck along largely unpaved roads - one of my colleagues asked me why I hadn´t written for so long in my blog (about 5 months). I fessed up. I had nothing good to say, so I chose to say nothing rather than broadcast my glass-half-empty POV. Her question inspires me to find another way to look at things. To try to see the glass half full. The glass is half full...really! Donald Donald So, with that idea in mind, here is the first of a series of things for which I am grateful, which have inspired me or at least leave me hopeful. Donald - a fisherman I meet Donald on one of my first trips to Quilali - one of a number of workshops to teach young leaders how to audit the work and spending of their local government, a skill of citizenship. A young, bright, skinny young man (in his 20s). Thoughtful, interested and confident, ready to tease me at the drop of a hat. We spend some time together and I discover he likes fishing. It´s a way to supplement his family´s protein intake. I tell him I will see if Dad has an old fishing rod he no longer needs that I can bring back on my next trip to the UK. It´s a promise. Donald helping young painters on a mural in the town.  Panning for gold in Quilali Panning for gold in Quilali Fast forward a few months, and Donald invites me up to see a small group of his young friends show me their theater work that they have developed around issues of diversity and tolerance in the local youth group. We take a walk with his sister to the river where he fishes. It´s wide, shallow and hard to imagine that it is rich in fish. Some young men are panning for gold (video at left). They dig in the banks and pan in the river. Occasionally they discover what little was left behind by the Spanish invaders.  I make the trip to the UK, ask my Dad for a fishing rod and bring it back with me from Wales to Nicaragua. I am busy traveling to Argentina to earn the money I spend volunteering, and I can't take it up to him personally. So my colleague takes ti for me and presents it to him in a semi-formal ceremony at the end of the workshop. His smile says it all!  I see Donald a number of time over the next few months, and I tell him I will come up to Quilali one day when the truck is taking one of the team up there to run a workshop. I also promise to ask my Dad for one of his fishing nets for him. Sadly I forget to do this when I go home to the UK. Something gets lost in translation, and he thinks I am going up to Quilali one week. He catches a fine fish for me using my Dad's rod. Has his Mother fry it for me. It´s a surprise for me. He brings it to the workshop only to find I don´t show up. The truck driver eats my fish. When I find out the next day, I am devastated and make a promise to join my colleague on her next visit to Quilali. Fast forward another month, and I am on the road again to Quilali. It´s the dry season, and the unpaved road is dusty. There is a chronic water shortage in Quilali and the surrounding communities. Many families must walk far to pull water form central wells. We pass young children, 7 or 8, pushing carts with plastic containers up impossibly steep hills. My heart goes out to them. A few hundred yards on, we pass a truck that is coming back from delivering beer. Two drivers munching down on breakfast sandwiches in their air-conditioned cab of the newish truck. There are only two brands of beer in Nicaragua, both of them like a bad American beer. The same family owns both breweries - a total monopoly. I am quietly fuming that the distribution system for beer is as near perfect as it can be, lining the coffers of one family, while water, none f it really potable, is in short supply and inconveniently located for women andyoug children to haul by hand.  When I get to Quilali, we look for my friend. He has just started a new job - looking after a cyber (where people rent computers by the hour for about 40 cents an hour). He has been looking for a job for ages. It pays the handsome salary of $80 per month, before taxes. He's happy. He has three small fish for me. But he tells me, with a sad look in his eye, that his Mother can't cook them for me, because she doesn't have any wood for the stove. I feel about an inch tall. People buy wood that has been illegally taken from the forested hills (a significant part of the problem of deforestation) to cook on adobe stoves such as the one shown on the right. Each stick of wood costs about 20 cents. Shortly before coming up to Quilali, I had remembered the promise of a fishing net. The price? About $150 - yes, that's double his monthly salary! So I balk at he idea of spending the equivalent of 750 pieces of cooking fuel on an over-priced, imported fishing net. I'll look for another way to fulfill my promise to Donald. A promise is a promise.  I am reading the book "Ancient Futures" and it captures beautifully what I have been thinking and experiencing here in Ocotal, and then a whole lot more. I am fascinacted by the book and I include a couple of excerpts here while I finish the last 50 pages. I could have waited, but what the author has to say seems too vital to wait. Home, Family and Communty I left home when I was eight to go to boarding school, and when I was 18 to work overseas, never to return home or to my family except for visits that could be measured in days rather than weeks. Helena writes: "...,I had thought that leaving home was part of growing up, a necessary step toward becoming an adult. I now believe that large extended families and small intimate communities form a better foundation for the creation of mature, balanced individuals. A healthy society is one that enoucrages close social ties and mutual interdependence, granting each individual a net of unconditional support. Within this nurturing framework, individuals feel secure enough to become quite free and independent."  An indigenous woman and her donkey in Ocotal An indigenous woman and her donkey in Ocotal The Impact of "Development" I am reading the book for two reasons: I am proposing to co-design a gender equality program for a series of 17 rural communitities; and we are about to launch a new diploma course in the Institute: "Leadership, Gender, and Culture". Helena talks a lot about the destruction of local culture through well-intentioned but occasionally thoughtless and often misguided development people. She quotes the Development Commissioner in Ladakh in 1981: "If Ladakh is ever going to be developed we have to figure out how to make people more greedy. You just can't motivate them otherwise." I took a metaphorical double take when I read that quote. 1981 was just when India was providing development support to open the region up for tourism. Sadly, development with its "messengers of development - tourists, advertisements, and film images" end up destroying local culture and sustainable practices. "Development is stimulating dissatisfaction and greed; in so doing , it is destroying an economy that had served the Ladakhis for more than a thousand years." Helena does not romanticize the old ways vs. the new, but she does actively question if there is not a blended solution to development (that's the part I am just reading).  The "mascot" of last year's horse parade The "mascot" of last year's horse parade How We Measure "Poor" The institute is part of a national discussion of how to define "poor" and what should be considered in determining if someone is poor or not. The traditional measure of social welfare of one country over another is often based on GNP. Helena writes: "Whether in remote subsistence economies or in the heart of the industrialized world, there is clearly something wrong with a system of national accounting that sees GNP as the prime indicator of social welfare. As things stand, the system is such that every time money changes hands - whether from the sale of tomatoes or a car accident - we add it to GNP and count ourselves richer. Policies that casue GNP to rise are thus often pursued despite their negative impact on the environment or society. A nation's balance sheet looks better, for instance, if all forests have just been cut to the ground, since felling trees makes money." This method of calculating "poor" and therefore spurring on "development" efforts leads to enthusiastic "development" and "modernization" which tend to be the same as "Westernization" and "industrialization", as described by Helena: "...the interaction of a narrow economic paradigm with continual scientific and technological innovation. The process has grown out of the past centuries of European colonialism and industrial expansion, through which our diverse world has been shaped by an increasingly uniform economic system - one that is dominated by the powerful interests of the industrialized countries, the multinational corporations and the Third World elite."  A donkey carrying cooking fuel A donkey carrying cooking fuel Those last few words catalyzed another metaphorical double-take. And got me thinking about something a friend said in the street while we watched this year's horse parade. All the riding clubs, schools and horse training centers bring out their prize horses and put them on display in a wonderfully and typically disorganized parade - quintessentially rural, central-american, small town. The riders were mostly the rich elite. The streets were filled with a mixture of people of all social levels, and the remaining rich elite in stands along the parade route, drinking from open bars. My friend, a peace-corps worker, had invited her host family to come with her to the parade. The family wouldn't go, it was only for "rich folk". My friend pointed out the parade was free. "Ah, but the children will want me to buy the things for sale along the street that I can ill afford. Rich folk's things. They will not be happy." My heart sank, saddened that such a lively event should be beyond the reach of so many in such a subtle way, something that would never have occurred to me. And I thought back to Helena's book...and the rest of the parade didn't seem quite so jolly.  The General Hospital in Ocotal The General Hospital in Ocotal Free Healthcare I burned my leg pretty badly about two and a half weeks ago and the wound is still infected but healing, very slowly, I think. I self-treated the wound for a few days, before I decided I was out of my depth and needed some more help. A friend took me to the local hospital to see the dermatologist. An organized emergency room of sorts, run by the government to provide free health care. It's a fairly simple system to get registered and after a couple of visits to a couple of desks, I see the dermatologist. Prescriptions for antibiotics, an antibiotic injection, an astringent powder and an antibiotic cream - all to be applied twice daily. I have heard a couple of stories about the hospital, one of which is that it is not uncommon to have 2-3 people to a bed and a chronic shortage of bedsheets. The facilities are certainly basic and we had to wait for the dermatologist and a co-worker to finish their breakafst of nacatamales (a local delicacy of ground cornmeal, meats and gravy all wrapped and boiled in the leaves of a plantain) before they would see anyone, about a half hour late. There isn't much hand washing as far as I can see, but the nurse did don rubber gloves to clean my wound. Getting the medications was a lesson in itself. You don't actually need prescriptions to get drugs in Nicaragua, but it helps to make sure people get the right things, which is why I think we are given them. You can get anything you need just by asking, which must be a nightmare to those who are trying to control excess use of antibiotics. They use them here like jelly beans. I bought everything in a pharmacy, including my own syringe. With goods in hand, I walked the street in search of a nurse. The first, who also ran a corner grocery store, no longer worked as a nurse. She recommended me to a second, who also no longer worked. From her to a third, who also owned a corner store. Luck was with us, she still worked. We entered through her side door. She took my antibiotic, the syringe, asked me to drop my pants and lay across her bed. In spite of her request being in Spanish, my mind immediately went to Dylan's song, "lay-lady-lay, lay across my big brass bed." Only this was just a mattress with some pretty suspect-looking sheets in a dusty, window-less room. The nurse was lovely: sweet, kind, gentle - just not quite the facilities I am used to back in the Fenway Health Center in Boston! P.S. I have a third, follow-up appointment for 8 am next Tuesday. They have a really simple scheduling system here. Everyone's appointment is at 8 am...everyone...you just wait until the doctor is ready to see you...or has finished her nacatamale!  One Man's Dung Is Another Beetle's Meal When I was fourteen, or so, I spent a weekend in a theater workshop pretending to be a dung beetle. The memory is still strong but incomplete. I don't remember where I was or if our ball of dung was imaginary or made out of wire and papier-mâché. I have memories of it being much larger than I was, whether imaginary or not. And why a dung beetle? I have no idea! We actors have always been on the fringe of cutting-edge self-development and self-discovery techniques.  Dung beetles collect dung in balls and roll them to their nests to feed their young. They also lie on top of them when it is too hot to keep themselves cool, the dung acting like a clay container filled with water - the evaporation of moisture cools the dung and the beetle cools his belly, much like a dog on a cold, kitchen floor. What's more, dung beetles roll their balls with their hind legs, their faces to the ground, basically backwards, and apparently with amazing accuracy. You can watch a video I took of a dung beetle if you click on the picture to the right. I came across this dung beetle on the unpaved road, walking from the Institute on my way to the mainroad to catch a taxi. I had never seen one before, but I immediately recognized what it was from my weekend of being one...albeit on a different scale. And I began to think that a dung beetle is an awesome metaphor for working as a novice the world of development in the America's second poorest, developing country. You are doing a good thing (dung beetles are the ultimate recycling machine at the bottom of the food chain), most of the time you don't know where you're going and you're doing it blind-folded (at least it often feels like that to me), and yet you are bringing good things to the local people (apparently the young beetles thrive on the stuff) while working at the base of the pyramid (where few people want to spend much time - Disneyworld and Las Vegas are much more attractive options). When I put it like that, I guess one never knows where a weird, theater workshop that one takes as a teenager might actually teach you something that you end up using some 40+ years later.  Queuing Is A Peculiarly British Thing I generally think I am pretty culturally flexible, bowing to cultural norms and bending as necessary to fit in, not rock the boat and become as inconspicioius as possible (another common British trait, desiring not to be noticed). One thing, however, I can not get used to is the complete lack of queuing here in Nicaragua, except outside banks on payday, where security guards with second-hand, Russian-looking machine guns guard the doors and frisk you with a metal detectors before letting you enter. I am quite sure they are not trained in either! There is absolutely no shame in cutting in, regardless of who is in line, or how old others are, or how infirm, or anything. People just push their way to the front as though nothing else matters in their world at that moment. It happened to me in the hospital. It happened to me in the pharmacy. Now I avoid conflict like the plague, my excuse being that I don't have the vocabulary to tackle some twerp who cuts in front of me, so I generally say nothing. The good news is, that this sad but true failing on my part (many therapists have failed to crack this one), is helped by the fact that I am about 9" taller than the average person, older and white. In other words, in a public hospital where the poorest people come for free care, I stick out like a sore thumb. Fortunately, the desk staff and the people behind the counter are better mannered, notice me in a second, and invite me to step into my rightful place. Which both feels good and bloody awful. On the one hand, I am where I should and I should be grateful that I am being taken care of. On the other, I feel like a cad and playing into expat stereotypes by taking advantage of my difference.  But more importantly, I wonder about the connection on the one hand between cutting in without a thought for others (i.e. a lack of courtesy in an otherwise courteous country), the sense of ownership of space and a clear sense of entitlement, with, on the other hand, the lack of resources here, the enormous and constant handouts (both from Jesus-teams, other volunteers and the government buying votes) and the total lack of care for the environment, both local and national. Very little is put in rubbish bins here. On the bus or in a car, anything and everything is tossed through the windows, nothing is recycled and aesthetics and concerns about environmental destruction are low on Maslow's hierarchy of needs in a country where many survive on less than $2 a day. And yet, I wonder if there isn't a connection here. People can be enormously courteous and gracious, and yet not. How might a little "Miss Manners" training play out in a larger context in terms of consideration of others and the impact of one person on another, both directly and indirectly. Bryant McGill wrote, somewhat darkly: “Courtesy is a silver lining around the dark clouds of civilization; it is the best part of refinement and in many ways, an art of heroic beauty in the vast gallery of man’s cruelty and baseness.” I think I prefer Ralph Waldo Emerson's words: “As we are, so we do; and as we do, so is it done to us; we are the builders of our fortunes.”  Typical adobe construction in rural houses Typical adobe construction in rural houses I've been thinking and talking a lot recently about the current approach to "development" as I see it based on the limited view I have from my remote corner of the world here in Nicaragua. My thoughts have been all stirred up by a number of recent experiences:

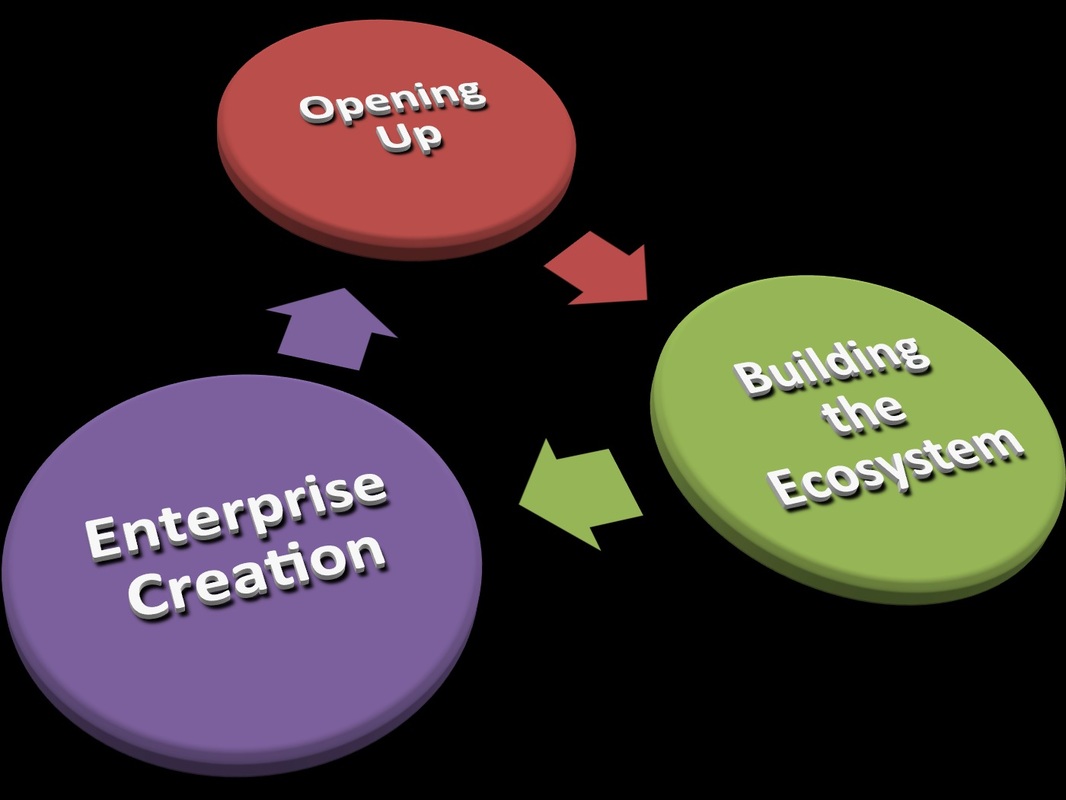

Let me begin with the last point, first, because I was interested to consider what other options there were to the current approach to development, which frankly seems to be failing as fast as developed countries get richer - an ever-widening gap. The books were recommended by a young American consultant working Brazil. I met him while facilitating a course in Leadership Presence, something I love to do and something that pays for my learning experience here in Nicaragua. I am leveraging my relationships with the rich to learn how to work with the poor. 4. Can capitalism save the world?Capitalism at the Crossroads: Aligning Business, Earth, and Humanity by Stuart L. Hart (2010, 3rd edition)  Claro and Movistar provide all cell phone coverage Claro and Movistar provide all cell phone coverage When I finished the books, I wrote the following note to the young consultant who had recommended them to me: "Hart was a fascinating read, although I vacillated between cynicism and optimism as I read his book. If nothing else, it opens up another way to look at things." In the second of the books I read, Prahalad closes his book with the following words (whcih I share at the risk of taking his words out of context): "...the real test of the entire development process is poverty alleviation. How will we know it is taking place? Simply stated, the pyramid must become a diamond. The economic pyramid is a measure of income inequalities. If these inequalities are changing, then the pyramid must morph into a diamond. A diamond assumes that the bulk of the population is middle class. ... Our Best allies in fighting poverty are the poor themselves. Their resilience nd perseverance must give us courage to move forward with entrepreneurial solutions to the problem. Given bold and responsible leadership from the private sector and civil society organizations, I have no doubt that the elimination of poverty and deprivation is possible by 2020. We can build a human society." Wow! A bold vision for what can be achieved by 2020, a mere 6+ years away. But what excited me more was a simple but thoughtful model from the other book by Hart, his BOP Protocol Process, which "...requires putting the corporate 'hammer' down and living alongside those in the community in a spirit of humility and mutual learning. It requires developing a personal relationship of trust, understanding, and respect through which new possibilities for locally-embedded businesses can emerge."

Hart explains this approach as follows: "Multinationals must expand their conception of the global economy to include the varied economic activities that occur outside the formal, wage-based economy. They must embrace informal economy, tailor their business models to enhance the way people currently live. Creating sustainable livelihoods means strengthening local communities and restoring the environment, not extracting resources and forcing people to move in the search of factory jobs. Spanning these worlds provides the basis for developing the climate needed for business to thrive by buidling respect for agreements, transaction transparency, and mutual trust." Is some version of new capitalism the solution? For me, Hart's protocol comes close to an "ideal" in spirit and methodology. However, the cynic in me doubts the ability of business leaders to reframe their role and the role of their people and their business, as well as challenge the current systems of share-holder reward. No matter how well-itentioned their efforts, I imagine share-holder pressure from both the existing investment community and the emerging middle classes will make this an (almost) impossible task. 3. How should we define "poor"? Children waiting to receive donated toys Children waiting to receive donated toys Everything I have considered so far is based on the idea of an enormous "base of the pyramid" that is defined as "poor", but it strikes me that the way we define "poor" is both flawed and in service of a traditional model of capitalism. Whose definition should we use? What would the diamond that Prahalad aspires to actually look like with a new definition that was not based only on income. At the same time as I was reading Hart, I subsequently discovered that ILLS is investigating this very question. What dimensions should we be measuring to define "poor"? The next books on my reading list are the following (sadly only one is available on Kindle): Ancient Futures: Lessons from Ladakh for a Globalizing World by Helena Norberg-Hodge, and 2. What makes Omotepe so special? Fountain in the park in Moyogalpa Fountain in the park in Moyogalpa I recently spent three days on the island of Omotepe, made up of two volcanoes, rising from Lake Nicaragua. The still-active volcano, Concepción (last major erruption in 2010) is the world's highest lake island and is considered the most perfectly formed volcano cone in Central America. Of all the places I have visited in Nicaragua, it feels like "Ometepinos", as the people on the island call themselves, are trying to create a tourist destination that avoids the excesses of San Juan del Sur, keeps the low-key attraction of Corn Islands, avoids the over-gentrification of Granada and has a sense of integrity with what the island naturally has to offer. In Nicaragua, this was a welcome find. Especially since every "Nica-owned" business was proudly touted. Clearly, there were expats who either owned or ran businesses, but you could hear the pride in people's voices when they worked for a "Nica" owner. I got to thinking about the role of tourism in creating sustainable development, though I'm not sure I have much of a point of view yet. 1. The irony of unequal access to gender equality training

What did I learn?

Camille Pissaro, c 1890 Camille Pissaro, c 1890 Once upon a time, there was a gardener who went from door to door, looking for work and a place to do what he loved to to do most of all: to turn ordinary places into beautiful places, full of vibrant colors, living plants and glorious flowers - a place where people, animals and insects could relax, refresh and rejuvenate in a shared space, each adding to and taking what they needed. He loved his somewhat itinerant life style, because along the way he met wonderful people who were interesting, different and kind. Everywhere he went he learned something new, because no two gardens were ever alike, each differing in what could be achieved because of the soil, the light, the rain and the wishes of the garden's owner. These differences he welcomed. These challenges kept him busy and open to new ideas.  Berthe Morisot, c 1884 Berthe Morisot, c 1884 After a long, winter season when he had struggled to find any real work, he wandered into a village one day and knocked on the door of a fine looking house with a large garden that looked like it was too much to care for. The owner answered the door. She asked for his name. "Juan," he told her. She asked him where else he had worked. He gave her the names of some other people he had worked for in a neighboring town. She recognized one of the families. They knew people in common and she felt more comfortable. He asked her for work. "Let me show you what I can do. Let me learn something new. Let me help you to grow a beautiful garden."  Claude Monet, c 1880 Claude Monet, c 1880 She paused, she looked at him and quietly said: "A beautiful garden needs love and you will need to put your heart into it. Let's see if you have the heart." They talked some more and brainstormed ideas, each sharing their dreams for the garden. It was a fine space in a good location and his mind was racing with the ideas of everything he could do - unlocking all the possibilities inherent in the soil, and the garden's position, its shape and its size. In the end, she said he could do the work, but that she didn't have much money to pay him. He didn't care! With such a wonderful opportunity and her support he could create a garden that would guarantee him his reputation in looking for other work. He would work for next to nothing, only with somewhere to sleep and food to eat. They had reached a deal, and the gardener settled in for the night before starting work the following day. What luck! What joy! He had never worked in a garden this large. This was the perfect situation and the following morning he started with all the enthusiasm of a young puppy who chews her master's slipper when she is out of the house. Which was just as well, because his employer left to go out of town the very next day. He started right in and began to bring to life the dream design they had created.  On Day 2 of his work, he met his employer's husband, and discovered he had some other ideas for the garden - a putting green to practice his golf. They had never discussed this, but he worked to include the man's wishes for the garden. On Day 3, the children came home from boarding school and wanted to play right where he was working. They wanted a tree house but they seemed to have little interest in what he was doing. He carried on regardless, firm in his desire to realize his and his owner´s dream design.  By Adrienne J. Kralick By Adrienne J. Kralick On Day 4, his employer returned to the house, with just enough time to glance at his progress from her bedroom window while she packed for her trip to leave that night for the family beach house. She waved from the window and gave him a "thumbs-up" sign of approval. On Day 5 of his work, with the family away at the beach house, he was surprised to see the neighbor standing in the driveway of the house. She wasn't happy with the changes he had made to the garden wall that bordered her house. She was going to speak to the owner just as soon as she got back. She might even talk to the town council and see what they had to say about all this. He rested on Days 6 and 7 and began to wonder if he hadn't taken on a project beyond his capabilities.  When he came back to work on Day 8 he was filled with energy and enthusiasm...at least until the visit of his employer's Mother. He didn't know that this was in fact her house, and not his employer´s. Could he show her the drawings? Where were the plans? What was the budget? Was he keeping all of the receipts and documenting where he was moving her precious plants? She wanted to see a paper trail of every detail. He was a gardener. His passion was creating life out of soil, creating beauty out of nothing, of unlocking the possibilities. He was not passionate about paper trails!  By Janice Trane Jones By Janice Trane Jones On Day 9 the family returned and there was chaos again with the children all over his lawn, his borders and climbing in his newly planted trees and shrubs. He had no one to turn to for help, because the owner was leaving the very same evening, this time for the city, staying in their other apartment. She had waved briefly to him from the bedroom window as she packed her bag for her trip. By Day 10, he had built the putting green for his employer's husband, but he showed no interest and hadn't even been out to look at his work. He wondered if he cared.  While working on Day 11, he recalled the conversation he had had with the owner before he started the work. Their dreams for the garden, their ideas, the possibilities. "Do you have the heart to do this?" she had asked him. He had the heart, he had reassured her. But he started to wonder where was the heart in this project. Where was her heart in the project. Did she really care, or was her mind elsewhere, in other projects, her interest split between many houses, too busy to notice or really care. Or was this a showpiece for her neighbors, as long as he didn't upset them! He worked on Day 12, but with less enthusiasm and more than a little disappointed. The neighbor came by with another complaint. He told her to talk to the owner - he was just following instructions. She left in a huff, scowling at his beautiful work. Which was unfair, because he had made good progress and of that he could be proud. The new shrubs and trees were settling in and looking more happy. The roses had clearly responded well to plant food and regular watering. And the lawn was beginning to look greener than it had ever looked. His expertise was paying off and the garden was responding to his green thumb! He rested on Day 13 and 14, and when he came back on Day 15 to continue to work, the owner came into the garden for the very first time in two weeks. She needed to talk to him, she said. The neighbor was not happy with the changes to the garden wall and her children were unhappy with the lack of space to play. Her husband, though he appreciated the effort, said the distances were too small on the putting green to be able to play. And her mother was worried that the changes were too drastic and not what she wanted.  By Van Gogh By Van Gogh That night, the gardener decided his work was largely wasted and not appreciated. He was putting his heart into the project, but the home and the family showed no love in return for the garden. Their heart wasn´t in it. They didn't seem to care. Perhaps too busy with other priorities and concerned about other things. Before the break of dawn the next day he left the house and strode out of the village, looking for other work. The garden continued to grow, but the scent of the roses was not quite as sweet, the grass not quite as green and the trees and shrubs not quite as tall as they might have been. Did they notice? Sadly not. The other houses and other projects distracted them from these small details. But if the plants could have spoken, they would have murmured their sadness, spoken of their loss. I am 10 days short of a year here in Ocotal, embedded for the first time in the world of "development". And my loosely-defined, altruistic ambitions have been challenged and I am disappointed. I am trying to work out how to make lemonade from the remaining lemons that haven't been spoiled. I have been debating with myself for days about how to write this blog, balancing a number of concerns:

No more debating! I will dive right in with some random though clearly connected thoughts and feelings, based on my clearly limited experience.

So I will try to sit with this discomfort and doubt and be present to today's opportunities, trusting that a loving and thoughtful approach will lead to some clarity. “At the end of the day, the questions we ask of ourselves determine the type of people that we will become.” Nature´s way of bringing in the winter (the rainy season) in Ocotal. We are surrounded by these glorious flowering bushes and trees, and the rains haven´t even come yet, and probably won´t for another 5 or 6 days. These were taken by en excellent photographer and dear friend - sadly not by me. |

BackgroundI sold house, car and most of my furniture to move to the small town of Ocotal in Las Segovias on the Honduras/ Nicaragua border. Archives

March 2014

Categories |

Contact© Copyright 2018 Richard Richards, Bournemouth, Dorset, UK

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed