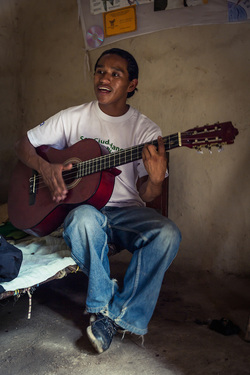

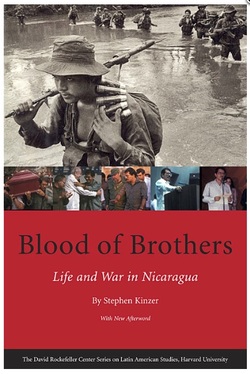

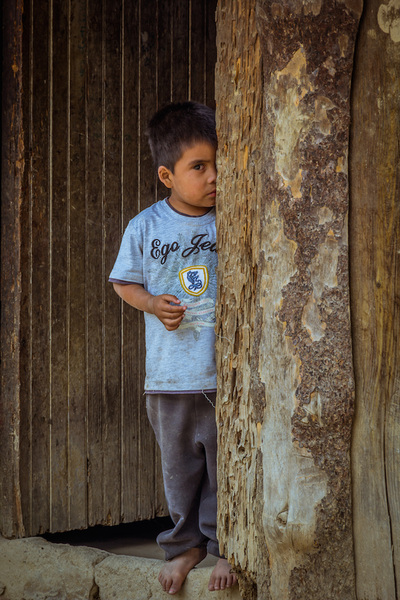

Cusmapa, Nueva Segovia, Nicaragua Lennin (photo by Osman Rivas) Lennin (photo by Osman Rivas) This is about a friendship I am grateful to have made... Lennin is from San José de Cusmapa, a town of about 7,000 people, close to the Honduran border and within sight of El Savador. It´s´a poor, rural community which is dry and short of water and work. The primary cash crop is coffee, which has all but been destroyed by disease. The remaining agriculture is subsistence. It is a town largely populated by indigenous people...people such as Lennin. I first met Lennin at a workshop in the institute where I volunteer. I was attracted to him more than others because he sings, simply and hauntingly, songs that are politically and/or socially motivated. He is passionate about the rights of indigenous people. He has no job (he works day jobs when he can get them), has very little money, and volunteers for the organization that represents indigenous people in Cusmapa...passionately. You can get a sense for his town by watching the short video at this link. I got to know Lennin's history when he took the 3-hour journey from his town to Ocotoal, a tedious journey along largely unpaved roads, that are only now in the beginning stages of being paved. I worked with him to create a website for the indigenous community of Cusmapa, something that felt like putting a contemporary "stake in the ground", although of little practical use in Nicaragua, where internet access outside the cities is limited and expensive for local people to buy, even if only by the hour.  The struggle of indigenous people in Nicaragua is probably not unlike many other countries, although the laws themselves seem pretty comprehensive here. However, I sense the application of the law may not always be so consistent. Lennin plays an active and passionate role in fighting for the rights of his people...especially through his music. So we also created a simple website for his music. You can sample his music (sung in Spanish), cheaply recorded on my Zoom H4 in a home-made recording studio in the flat I rent in Ocotal. Click here to hear his songs. Given the right equipment and someone who knows what he or she is doing, and it would sound a whole lot better.  Tona, Lennin's Mum (photo by Osman Rivas) Tona, Lennin's Mum (photo by Osman Rivas) It never ceases to amaze me that the when poor people are generous, their contribution seems so much greater than when rich people are generous. Which may not be fair, but proportionally, their contribution is much larger. Tona, Lennins's Mum, with little enough money to feed the family she had, adopted a young, under-nourished boy into the family and lavished him with love and a home. Working with the Fabretto organization, you can see a short video of the boy, Gabriel, and Tona at this link. The video provides a sense of the humble and happy home Gabriel has joined. A few years later, this video was made by the Fabetto organization, to show Gabriel's progress. It is a touching video and beautifully produced. Sadly it is not sub-titled, but if you understand Spanish, expect to shed a tear or two. The video is mixture of sadness, joy and unconditional love. The cynic in me could poo-poo the video as a manipulative promotional piece by a big NGO. But having visited the town, met and spent time with the family, and having eaten with Gabriel and Tona (beans, cheese and home-made corn tortillas, hot off the wood-burning stove), nothing bout the video is inauthentic. More to the point, Tona's every bit as beautiful as she is in the video. I am grateful for the rich opportunity to know Lennin because I am beginning (and I mean "beginning") to understand the roots of his plight and the plight of poor rural and indigenous people in Nicaragua.  The author, Kinzer, describes how Cesar Sandino's 1927-33 anti-U.S. campaign shaped the country's political development and inspired the overthrow of the Somoza regime in 1979. He analyzes the Reagan administration's "secret war" against the Sandinistas, and the deception that the contras existed only to interdict arms shipments to El Salvador. He paints a devastatingly sad and depressing picture of corruption, ineptitude and power-struggles. Reading the book, it would have been easy to sink into despair, had it not been for the resilience of Nicaragua's people. And a sense of compassion for the situation in contemporary Nicaragua. I am not a patient man In fact ,in an evaluation of my work here in the institute over the last two years (a team-wide, 360, in person evaluation - something you could never pull off in most corporate environments), my lack of patience and my lack of appreciation of Nicaraguan history and culture were my most significant learning edges. And I thought, wrongly as it seems, that this would be a strength after living overseas for 38 years! I could defend my intention (which clearly wasn't the "impact") as high expectations for what I thought was possible. However, reading this book just as I am about to leave, it is really helping me to reframe my disappointment as I begin to understand the history of this country. So I am grateful for the opportunity to know Lennin, his family - their daily joys and their daily struggles. What I experience through them in real life brings more of the words of the Kinzer's pages to life.

2 Comments

I am about 3 weeks away from leaving Nicaragua. When I leave, I will have been here for just under two years... I sold house, car and most of my furniture to relocate to one of the poorest regions of the country to build out my resume with experience working at the bottom of the pyramid, while contributing in some small way to an institute that seemed a perfect match to my previous experience, which was working at the top of the pyramid, and my future thinking, to work in some small way to close tha gap between the top and the bottom. I will leave feeling disappointed, defeated and just a little lost. The fault is not the institute where I have worked, but the bigger development system and political environment within which they so diligently work. Since I view the bigger system completely broken, I therefore see myself in any role within the system as aiding and abetting the problem. I´m not sure how to change it. On a recent trip to Quilali - a remote rural town about 2.5 hours away by truck along largely unpaved roads - one of my colleagues asked me why I hadn´t written for so long in my blog (about 5 months). I fessed up. I had nothing good to say, so I chose to say nothing rather than broadcast my glass-half-empty POV. Her question inspires me to find another way to look at things. To try to see the glass half full. The glass is half full...really! Donald Donald So, with that idea in mind, here is the first of a series of things for which I am grateful, which have inspired me or at least leave me hopeful. Donald - a fisherman I meet Donald on one of my first trips to Quilali - one of a number of workshops to teach young leaders how to audit the work and spending of their local government, a skill of citizenship. A young, bright, skinny young man (in his 20s). Thoughtful, interested and confident, ready to tease me at the drop of a hat. We spend some time together and I discover he likes fishing. It´s a way to supplement his family´s protein intake. I tell him I will see if Dad has an old fishing rod he no longer needs that I can bring back on my next trip to the UK. It´s a promise. Donald helping young painters on a mural in the town.  Panning for gold in Quilali Panning for gold in Quilali Fast forward a few months, and Donald invites me up to see a small group of his young friends show me their theater work that they have developed around issues of diversity and tolerance in the local youth group. We take a walk with his sister to the river where he fishes. It´s wide, shallow and hard to imagine that it is rich in fish. Some young men are panning for gold (video at left). They dig in the banks and pan in the river. Occasionally they discover what little was left behind by the Spanish invaders.  I make the trip to the UK, ask my Dad for a fishing rod and bring it back with me from Wales to Nicaragua. I am busy traveling to Argentina to earn the money I spend volunteering, and I can't take it up to him personally. So my colleague takes ti for me and presents it to him in a semi-formal ceremony at the end of the workshop. His smile says it all!  I see Donald a number of time over the next few months, and I tell him I will come up to Quilali one day when the truck is taking one of the team up there to run a workshop. I also promise to ask my Dad for one of his fishing nets for him. Sadly I forget to do this when I go home to the UK. Something gets lost in translation, and he thinks I am going up to Quilali one week. He catches a fine fish for me using my Dad's rod. Has his Mother fry it for me. It´s a surprise for me. He brings it to the workshop only to find I don´t show up. The truck driver eats my fish. When I find out the next day, I am devastated and make a promise to join my colleague on her next visit to Quilali. Fast forward another month, and I am on the road again to Quilali. It´s the dry season, and the unpaved road is dusty. There is a chronic water shortage in Quilali and the surrounding communities. Many families must walk far to pull water form central wells. We pass young children, 7 or 8, pushing carts with plastic containers up impossibly steep hills. My heart goes out to them. A few hundred yards on, we pass a truck that is coming back from delivering beer. Two drivers munching down on breakfast sandwiches in their air-conditioned cab of the newish truck. There are only two brands of beer in Nicaragua, both of them like a bad American beer. The same family owns both breweries - a total monopoly. I am quietly fuming that the distribution system for beer is as near perfect as it can be, lining the coffers of one family, while water, none f it really potable, is in short supply and inconveniently located for women andyoug children to haul by hand.  When I get to Quilali, we look for my friend. He has just started a new job - looking after a cyber (where people rent computers by the hour for about 40 cents an hour). He has been looking for a job for ages. It pays the handsome salary of $80 per month, before taxes. He's happy. He has three small fish for me. But he tells me, with a sad look in his eye, that his Mother can't cook them for me, because she doesn't have any wood for the stove. I feel about an inch tall. People buy wood that has been illegally taken from the forested hills (a significant part of the problem of deforestation) to cook on adobe stoves such as the one shown on the right. Each stick of wood costs about 20 cents. Shortly before coming up to Quilali, I had remembered the promise of a fishing net. The price? About $150 - yes, that's double his monthly salary! So I balk at he idea of spending the equivalent of 750 pieces of cooking fuel on an over-priced, imported fishing net. I'll look for another way to fulfill my promise to Donald. A promise is a promise. |

BackgroundI sold house, car and most of my furniture to move to the small town of Ocotal in Las Segovias on the Honduras/ Nicaragua border. Archives

March 2014

Categories |

Contact© Copyright 2018 Richard Richards, Bournemouth, Dorset, UK

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed